Japan has many regional specialty dishes using everyday ingredients. Soy beans form an integral part of Japanese cooking, and over time a wide variety of preparation methods have created a vast range of textures and tastes specific to various regions throughout Japan. What can we learn by looking at these regional dishes that can inspire us to create new and interesting plant-based foods that appeal to consumers outside of Japan?

In this review of soybeans in traditional Japanese dishes, Dr Sonoko Ayabe of Takasaki University of Health and Welfare, Faculty of Health and Welfare, Department of Nutrition, Gunma, Japan introduces some dishes that combine different preparation methods and ingredients combinations to diversify the texture and taste of soy-based foods.

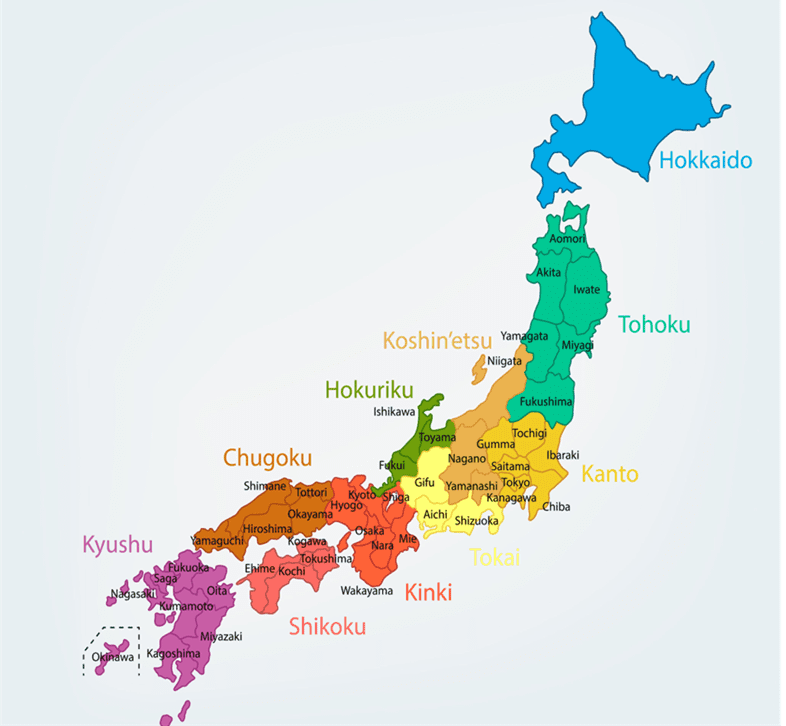

But first, here is a map of Japan to give you an idea of where some of the dishes mentioned below come from.

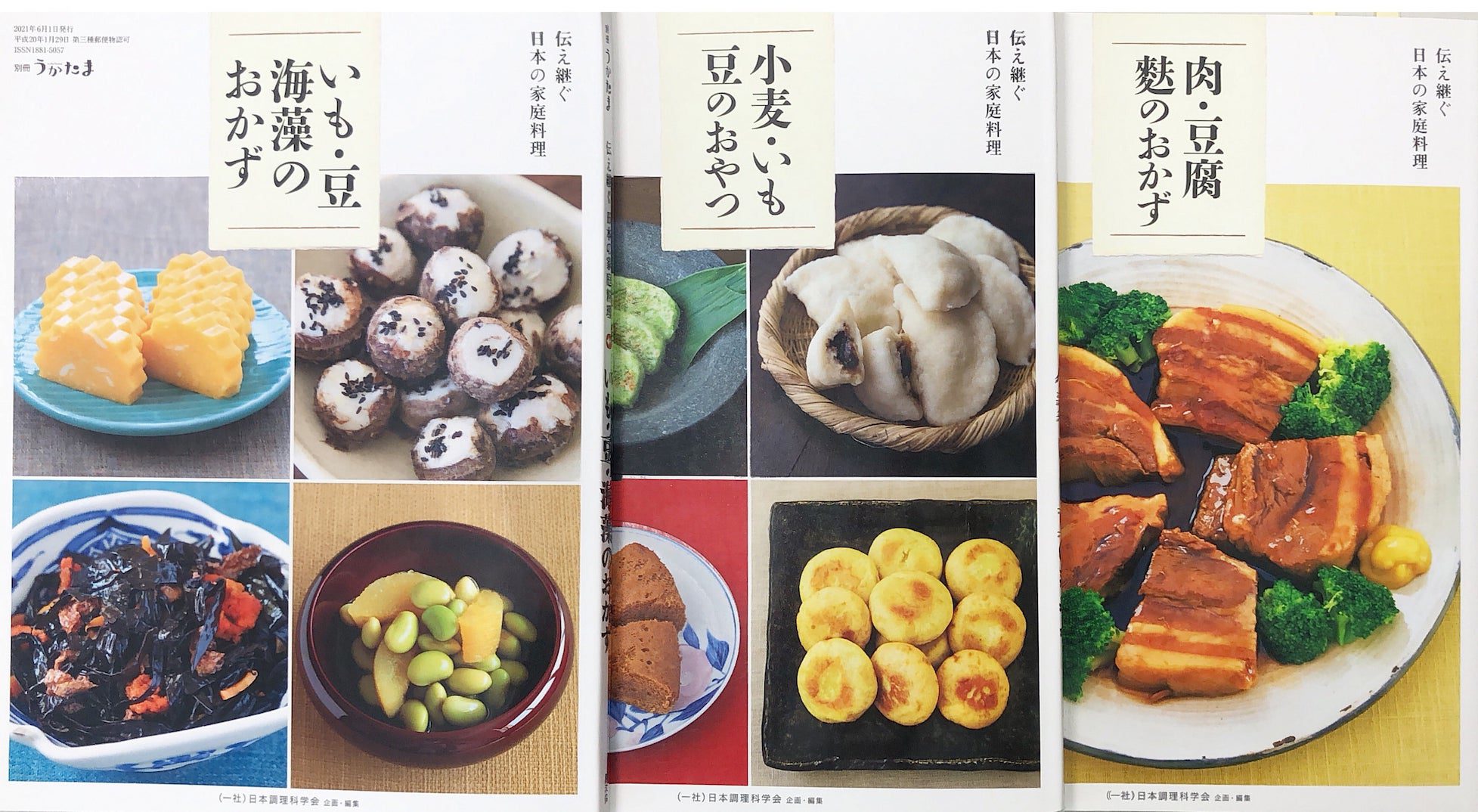

Soybean cultivation in Japan is said to have started in the Yayoi period (300 BC to AD 300). Today, soybean is prepared or processed in a variety of ways and is an indispensable part of the Japanese diet. Here I consider how soybean has been used in Japanese home cooking through an examination of Japanese Home Cooking Dishes to Hand Down to the Next Generation (planned/edited by Japan Society of Cookery Science; published by Rural Culture Association Japan). Japanese Home Cooking Dishes to Hand Down to the Next Generation (Fig.1) is a book series consisting of 16 volumes. Soybean or soybean products are featured in the titles of three of these volumes: “Main Dishes Using Tubers, Beans, and Seaweed,” “Snacks Using Wheat, Tubers, and Beans,” and “Main Dishes Using Meat, Tubers, and Wheat Bran.”

(Fig.1, Japanese Home Cooking Dishes to Hand Down to the Next Generation. From the left,“Main Dishes Using Tubers, Beans, and Seaweed,” “Snacks Using Wheat, Tubers, and Beans,” and “Main Dishes Using Meat, Tubers, and Wheat Bran.”)

Dried soybeans can be stored for long periods of time. To prepare dried soybeans for cooking, the beans are typically soaked overnight or roasted without soaking. One way to reduce the time needed for rehydration is to use uchi-mame [literally, “hit beans”]. Preparation of uchi-mame involves pouring boiling water over the beans, mashing them with a wooden mallet, and then drying the resulting paste. Uncooked soybean flour prepared by milling dried soybeans is also used in some parts of the country.

The volume titled “Main Dishes Using Tubers, Beans, and Seaweed” introduces several nimono [simmered] dishes that involve boiling dried soybeans and then simmering them with a variety of flavor ingredients, such as simmered kombu [seaweed] and soybean (Hokkaido, Fig.2), simmered soybean (Fukui Prefecture), gomoku-mame [mixed beans] (Ehime Prefecture), and zazen-mame (Kumamoto Prefecture). The volume also introduces marinaded dishes using either boiled or roasted soybeans, including spicy soybean (Hokkaido), marinaded beans (Miyagi Prefecture), vinegared black bean (Yamagata Prefecture), and vinegared soybean with dried cuttlefish. Also included are a simmered dish using uchi-mame known as kojiwari (Fukui Prefecture) and two dishes using uncooked soybean flour, one of which is a simmered dish with uchigo dumplings (Tottori Prefecture) and the other a soybean curd dish called igisu-tōfu (Ehime Prefecture). Finally, the book introduces dishes such as simmered miso (Mie Prefecture), a miso that is eaten directly, and kure-ae (Kyoto Prefecture), which is made with mashed boiled edamame [immature soybeans in the pod]. Although boiled and simmered soybean dishes are found throughout Japan, various preparation methods such as marinating or pickling with vinegar are used in different parts of the country.

(Fig.2, simmered kombu [seaweed] and soybean)

The volume titled “Snacks Using Wheat, Tubers, and Beans” introduces snacks that made from soybean or soybean products such as tofu and kinako [roasted soybean flour]. These include snacks made by mixing boiled soybean mash with rice flour such as mame-suttogi (Iwate Prefecture, Fig.3) and mame-shitogi (Aomori Prefecture), snacks made by mixing roasted soybean with mochi rice such as mame-kogori (Aomori Prefecture), and snacks made by mixing roasted soybean with rice or wheat flour, including kofuku-mame (Shiga Prefecture), mame-dago (Kumamoto Prefecture), and tokujiri (Shizuoka Prefecture). Snacks using tofu include tōfu castella and tōu-maki (Akita Prefecture), which are made by mixing tofu, sugar, eggs, and kinako, and kankan-bo (Gifu Prefecture), which is made by mixing kinako, brown sugar, and water.

(Fig.3, mame-suttogi)

The volume titled “Main Dishes Using Meat, Tubers, and Wheat Bran” introduces dishes made with tofu and okara [soy pulp]. Tofu dishes from different areas of the country are described, including tsuto-dōfu [tofu simmered in a straw wrapper] (Fukushima and Ibaraki Prefectures, Fig.4A&4B), komo-dōfu (Gifu and Tottori Prefecture), and shime-dōfu (Wakayama Prefecture). In the past, tofu was an expensive ingredient for common people. Tsuto-dōfu and komo-dōfu, which require substantial additional work to prepare, were special treats served on New Year’s or somber occasions.

(Fig. 4A , tsuto-dōfu [tofu simmered in a straw wrapper].

Fig.4B (Right), inside of tsuto-dōfu)

A variety of simmered tofu dishes are introduced, including kōsen-dōfu [tofu simmered in mineral spring water] (Gunma Prefecture), which takes advantage of tofu’s tendency to coagulate and is characterized by a soft texture and mineral spring flavor, tōfu-okaka-ni [tofu firmed by boiling and simmered in broth with bonito flakes] (Tokyo), kokusho [a dish featuring firm tofu] (Ishikawa Prefecture), tōfu-dengaku [grilled tofu basted with sweet miso] (Aichi Prefecture), tsushima [a dish using toasted tofu] (Yamaguchi Prefecture), yose-dōfu [crushed tofu gelled using agar] (Niigata Prefecture), and na-dōfu [tofu made with seasonal vegetables] (Miyazaki Prefecture, Fig.5). Dishes using okara, which are the dregs left after making tofu, include okara-no-taitan made by simmering okara (Kyoto Prefecture), kirazu- no-ogoyoshi (Saga Prefecture), kara-namasu [vinegared okara] (Chiba Prefecture), and various types of sushi rice cakes with okara, including omanzushi (Shimane Prefecture), azuma (Hiroshima Prefecture), okara-zushi (Yamaguchi Prefecture), maru-zushi (Aichi Prefecture), houkaburi (Kochi Prefecture), and okame-zushi (Nagasaki Prefecture).

(Fig.5, na-dōfu [tofu made with seasonal vegetables]

Dishes that appear in other volumes include rice dishes using roasted tofu such as narajako-han [crushed roasted soybeans and anchovies cooked with rice] (Hyogo Prefecture) and fukidawara [rice with roasted soybean wrapped in a giant butterbur leaf] (Nara Prefecture, Fig.6). Simmered uchi-mame dishes include nisai (Niigata Prefecture) and hyōboshi-no-nimono (Yamagata Prefecture). Uchi-mame soups include yamamochi (Niigata Prefecture), tōyamakabu-no-misoshiru (Yamagata Prefecture), and uchi-mame-jiru (Shiga Prefecture). These soups take advantage of the ease of making broth with uchi-mame. Finally, kure-jiru, a soup using kure [mashed soybean paste], is found in a number of places across Japan (Fukui, Okayama, Tottori, and Kumamoto prefectures).

(Fig.6, fukidawara, *1)

Although space limitations do not permit a complete discussion of every dish, the series also introduces numerous dishes using soybean products such as kinako [Fig 7, roasted soybean flour], natto [fermented soybeans], abura-age [thinly sliced fried tofu], atsu-age [thick fried tofu], kōya-dōfu [Fig 8, freeze-dried tofu], kōri-dōfu [frozen tofu], miso [fermented soybean paste], and edamame (Fig 9).

Fig 7: Kinako – roasted soybean flour

Fig 8: Koya-dofu – freeze-dried tofu

Fig 9: Eda mame – green soy beans

Soybean and soybean products have long been a valuable source of protein for the Japanese people, and a wide variety of soybean-based dishes can be found on many a Japanese dinner table. It is my hope that traditional dishes made with soybeans will continue to be handed down to future generations in Japan.

*1; https://www.pref.nara.jp/item/196403.htm#itemid196403